Once upon a time in a quaint village in Assam, there lived a kind-hearted and beautiful girl named Tejimola. Her father, a merchant named Mahendranath, loved her dearly, but her mother had passed away when she was young. Hoping to give Tejimola a mother’s care, Mahendranath remarried a woman who, unbeknownst to him, harbored a cruel heart. This stepmother, driven by jealousy of Tejimola’s beauty and her father’s affection, pretended to care for her in his presence but revealed her true nature when he was away. One day, Mahendranath had to leave for a long business trip. As soon as he departed, the stepmother’s cruelty emerged. She forced Tejimola to do grueling chores, starved her, and punished her for the smallest mistakes. The stepmother’s envy grew, and she devised a wicked plan to rid herself of Tejimola, especially as the girl was nearing marriageable age.

Tejimola was invited to a friend’s wedding, and to her surprise, the stepmother allowed her to go. She packed a bundle for Tejimola, claiming it contained fine clothes and jewelry, but warned her not to open it until she reached the venue. Trusting her stepmother, Tejimola obeyed. When she arrived and opened the bundle, she found only tattered rags and broken trinkets which was a cruel trick by her stepmother. Frightened of her stepmother’s wrath, Tejimola borrowed a dress from a friend and attended the wedding, but her heart was heavy with dread. Upon her return, the stepmother’s fury erupted. She accused Tejimola of ruining the clothes and, as punishment, forced her to pound rice on a dheki, a heavy wooden rice pounder. As Tejimola worked, the stepmother deliberately caused her hand to slip under the dheki, crushing it. Ignoring Tejimola’s cries, she demanded the girl use her other hand, then her feet, crushing them too. Finally, in a fit of rage, the stepmother crushed Tejimola’s head, killing her. She buried the girl’s body in the backyard and told the neighbors Tejimola had gone to visit a friend.

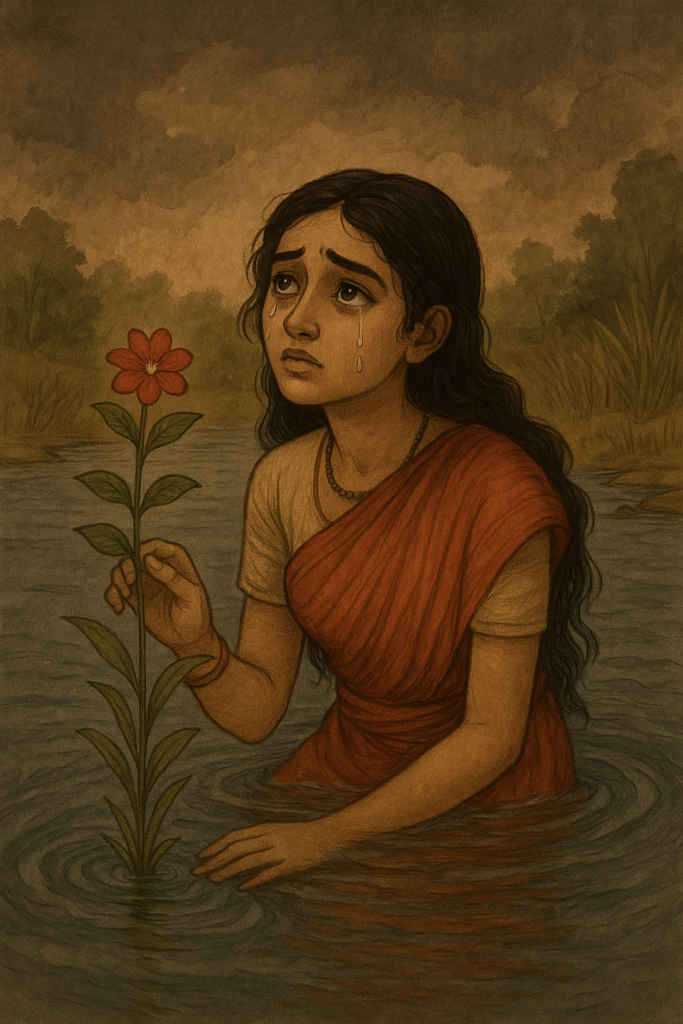

But Tejimola’s spirit refused to be silenced. From the spot where she was buried, a bottle-gourd plant sprouted. One day, an old beggar woman came to the house and asked for a gourd from the garden. The stepmother, unaware of the plant’s origin, allowed it. As the beggar reached to cut a gourd, a haunting voice sang, “Don’t pluck me, old woman, I am Tejimola, killed by my stepmother and buried here.” Terrified, the beggar told the stepmother everything, who, enraged, uprooted the plant and threw it into a far corner of the garden. After some time, from that discarded spot, a plum tree grew. Travelers passing by asked to pluck its fruits, and again, the same voice sang, revealing Tejimola’s fate. The stepmother, now frantic, uprooted the tree and cast it into a river. In the river’s shallow pool, a beautiful lotus bloomed. A fisherman, seeing the lotus, tried to pick it, and once more, Tejimola’s voice echoed her tragic story.

The fisherman ran to Mahendranath, who had just returned from his journey. Heartbroken but hopeful, Mahendranath went to the river and called out to the lotus, “If you are truly my Tejimola, become a myna bird and perch on my hand.” The lotus transformed into a myna, and as it landed on Mahendranath’s hand, it turned back into Tejimola, alive and whole. She tearfully recounted her stepmother’s cruelty. Furious, Mahendranath confronted his wife, who, overcome with guilt and fear, fled the village, never to return. Tejimola, now free, chose not to marry despite her father’s wishes. Having tasted freedom through her transformations as a plant, a tree, a flower, and a bird, she embraced her independence, living as a symbol of resilience and the triumph of goodness over malice.

Our takeaways

In Assamese culture, Tejimola’s story reflects the values of kindness, justice, and the deep connection to nature, teaching that even in the darkest times, virtue and hope can prevail. Tejimola’s suffering at the hands of her stepmother highlights the issue of domestic abuse and the mistreatment of vulnerable individuals, often within families. In 2025, global awareness of child abuse and domestic violence has grown, with initiatives like India’s National Commission for Women reporting a rise in complaints over 25,000 in 2024 alone as per recent web data. Tejimola’s resilience, as she transforms and survives, mirrors the strength of survivors today who overcome trauma, supported by modern movements advocating for mental health and survivor rights. Her choice to remain unmarried and independent at the story’s end challenges traditional expectations of women. This aligns with the ongoing discussions on gender roles in India and globally. Women are increasingly prioritizing autonomy, with data from the 2024 National Family Health Survey showing a rise in female-led households in Assam (up to 14% from 10% in 2019). Tejimola’s story inspires women to seek self-determination in a world still grappling with patriarchal norms.

Tejimola’s transformations into natural elements – a plant, tree, a lotus flower – reflect a deep bond with nature, a value central to Assamese culture. As climate change accelerates (with India facing record heatwaves and floods as per recent reports), this aspect of the story underscores the need for environmental stewardship. It reminds us of indigenous wisdom that sees humans and nature as interconnected, a principle echoed in modern sustainability movements. The stepmother’s eventual exposure and flight symbolize the triumph of justice. Tejimola’s story reflects the universal desire for wrongdoers to face consequences, a sentiment that fuels modern activism. As globalization spreads, stories like Tejimola’s help preserve cultural identity. Her tale, shared across generations, reinforces pride in Assamese traditions while addressing universal human struggles. In essence, Tejimola speaks to today’s challenges by highlighting resilience, independence, environmental harmony, justice, and cultural pride – values that remain critical in navigating the complexities of 2025.